|

Journal Home Contents Preview Next |

Pro Otology

Balkan Journal of Otology & Neuro-Otology, Vol. 2, No 1:14-17 © 2002

All rights reserved. Published by Pro Otology Association

Surgery for Facial Nerve Palsy

Milan Stankovic

ORL Clinic, Medical Faculty Nis, Serbia, Yugoslavia

ABSTRACT

Hypothesis: Etiology, type and intensity of facial nerve lesion determine the type of therapy and outcome.

Background: Facial nerve palsy can be important complication of surgery of temporal bone, parotid gland and skull base. Adequate surgical treatment can reduce negative effects of such injuries. Surgical treatment usually consists of nerve decompression, nerve anastomosis and graft technique with n. auricularis magnus.

Methods: Retrospective analyze of 258 patients treated for facial nerve palsy in ENT Clinic Nis during the period of 10 years was performed. The patients were divided in groups according to etiology and intensity of facial damage. Clinical examination, topodiagnostic, electrodiagnostic and radiography were routinely applied. House Brackmann scale was used for evaluation of results of medicamentous and surgical therapy.

Results: Totally 17,1 % of patients were treated by surgery. Iatrogenic facial palsy was present only in two cases out of 327 patients operated for chronic otitis media (0,6%). Traumatic facial palsy was mainly incomplete (62,9%) with frequent other otologic symptoms. Temporal bone fracture was verified in 88,6% of patients and intraoperatively lesion of nerve was predominantly suprastapedial (69,2%). Edema of nerve and fracture line were usually found. Different surgical techniques were applied (decompression in 84%, termino-terminal anastomosis in 9% and nerve graft in 7% of cases). Recovery of facial function was good and fast in idiopathic cases, with significant difference between complete and incomplete palsy. In surgical cases the best recovery was achieved with decompression, while nerve anastomosis and nerve graft had similar time course and outcome in House grades.

Conclusion: Residual changes are highly significantly more frequent in the group with complete idiopathic palsy. Surgical therapy in selected cases of peripheral facial palsy gives well results. Decompression of nerve is significantly more effective than nerve anastomosis and nerve graft, concerning both time and outcome. The type of surgery and results depend on the etiology, intensity, site and time of treatment of facial palsy.

Key Words: Facial nerve, Facial nerve palsy, Surgery.

Pro Otology 1: 14-17, 2002

INTRODUCTION

Facial palsy causes disfigurement of face in rest and during activities and social and psychological consequences as well. The patients can not express anger, surprise, anxiety, disgust, fear, happiness, and many other important emotions. They have both impairment and disability caused by facial palsy. Impairment is defined as psychological and anatomic abnormality of organ or tissue. Disability means inability to perform usual activities.

Electron microscopy of facial damage indicates on: degeneration of myelin sheath, axon cylinder, swelling, compression of vascular channels, lymphocytic infiltration, phagocytic cells, proliferation of endoneurium, and increase of connective tissue. Recovery of nerve injury is characterised by reversal of these changes.

Different tests are used for evaluation of status, study the effects of therapy and prediction of course during peripheral facial palsy. They can be divided on observer-based rating scales and motion analysis. However, there is no universally accepted simple and reliable test. There are no tests based on patient's perception of condition (1-3).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Retrospective analyze of 258 patients treated for facial nerve palsy in ENT Clinic Nis during the period of 10 years was performed. The patients were divided in groups according to etiology and intensity of facial damage. Clinical examination, topodiagnostic, electrodiagnostic and radiography were routinely applied. Surgical treatment comprised of nerve decompression, nerve anastomosis and graft technique with n. auricularis magnus. House Brackmann scale was used for evaluation of results (4).

Obtained results were studied statistically with Students t-test for p<0,05.

RESULTS

Totally 17,1% of patients were treated by surgery (3% with idiopathic, 37% with traumatic, 100% with inflammatory, 78% with temporal bone tumors, 20% with herpes zoster oticus, and 100% of pontocerebellar and parotid tumors and iatrogenic injuries) (Table 1).

Iatrogenic facial palsy was present only in two cases out of 327 patients operated for chronic otitis media (0,6%). The damage was caused by dehiscence of nerve in tympanic part and extensive cholesteatoma. Immediate nerve reconstruction was performed, and late results were acceptable (House grade II-III) (Table 2).

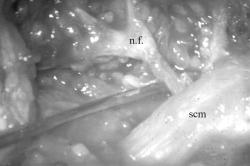

Traumatic facial palsy was mainly incomplete (62,9%) with frequent other otologic symptoms. Temporal bone fracture was verified in 88,6% of patients (Table 3). Intraoperatively lesion of nerve was predominantly suprastapedial (69,2%). Edema of nerve and fracture line were usually found. Accordingly different surgical techniques were applied (decompression in 84%, termino-terminal anastomosis in 9% and nerve graft in 7% of cases) (Table 4),( Fig.1, Fig. 2).

Recovery of facial function was good and fast in idiopathic cases, with significant difference between complete and incomplete palsy (Histogram 1). In surgical cases the best recovery was achieved with decompression, while nerve anastomosis and nerve graft had similar time course and outcome in House grades (Histogram 2).

DISCUSSION

The range of facial palsy caused by chronic otitis media before the antibiotic era was 1,2%, and after antibiotic era it has been reduced to 0,2%. If cases with cholesteatoma are analyzed separately, than facial palsy produced by the disease itself is about 1 %.

|

|

|

Histogram 1. Time course of idiopathic facial palsy judged by house grading system. |

|

|

Histogram 2. Time course of traumatic facial palsy and type of rsugery judged by house grading system. |

It is generally accepted that the risk to the facial nerve during temporal bone surgery is present, but there is difference in opinion how big it is. For primary chronic otitis operations it amounts from 0,2% to 3,6%, while in revision cases it is much higher up to 4-10%. From this data it is clear that the risk of developing facial nerve complications from untreated disease is similar to the risk of middle ear surgery. This implies the need for adequate preoperative information of the patients concerning benefit and potential complications during chronic otitis surgery. On the other hand, reference data and our results show that careful surgical technique and adequate experience can maximally reduce the rate of intraoperative facial palsies. If facial nerve injury occurs immediate decompression, anastomosis and grafting should be done in order to achieve the best final results (5-8).

The most common procedure during which the injury of facial nerve occurred is mastoid surgery, but cases with myringoplasty and removal of exostosis were also described. The most of nerve injuries are noted immediately during surgery, there are series of patients where damage was not detected at the time of surgery.

Dehiscence of facial canal can be found in 5-30% of analysed temporal bones and can be an important factor for producing iatrogenic facial nerve injury (oval window niche, around cochleariform propagation, vertical part of nerve). Iatrogenic facial damage can be found in: reoperation of chronic otitis, malformations of ear and facial course (nerve over oval window, bifid nerve), and inadequate surgical technique (narrow access, bad visibility, bad haemostasis, transversal bone work, inadequate burr, nerve traumatisation).

Sure identification of facial nerve can be accomplished with: wide surgical field, good hemostasis, suction, and parallel drilling with diamante burr. Nearly all parotid, temporal and otoneurologic surgery demands identification and liberation of facial nerve. So, it is the best to find facial nerve in healthy region, use of operation microscope, and nerve stimulator if possible. Each soft tissue in oval window niche should be considered as facial nerve hernia, until proven different (5-8).

Most of the cases with traumatic facial palsy are caused by traffic accidents. Usually the nerve deficit is seen immediately, except in cases with unconscessness.

The extent of facial nerve injury in some cases directs to use of grafting technique. The final result of direct anastomosis or grafting was House grade III and IV, what is significantly worse than nerve decompression where the most of outcomes were House grade II.

|

|

|

|

FIG. 1. B. The tympanomeatal flap is elevated and the superior bony canal wall widened with the diamond burr to expose the anterior tympanic spine. |

FIG. 1. B. The tympanomeatal flap is elevated and the superior bony canal wall widened with the diamond burr to expose the anterior tympanic spine. |

Neurosuture of facial nerve can be immediate and delayed. Immediate one demands clean surgical wound, and uncontaminated trauma. Delayed suture is used for contaminated wound, projectile injury, and bad general condition. Preferred surgical methods are: termino-terminal anastomosis, rerouting, interposition of transplant, XI or XII cross over, and neuromuscular transfer. Local causes of failure after neurosuture are: proximity of lesion to stylomastoid foramen, period of delay, number of anastomoses, and infection. Surgical factors of success are: no nerve tension, adequate position of nerve ends, minimal debridment, and minimal number of atraumatic sutures (9-12).

In general, facial nerve surgery is directed to obtaining facial symmetry at rest, balanced movements of upper and lower half of the face for willing and unwilling movements. This can be achieved in most of the cases with acceptable results.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Good recovery of function was achieved in 73% with incomplete, and in 38% with complete idiopathic facial palsy. Residual changes are highly significantly more frequent in the group with complete palsy.

2. Surgical therapy in selected cases of peripheral facial palsy gives well results.

3. Decompression of nerve is significantly more effective than nerve anastomoses and nerve graft, concerning both time and outcome.

4. The type of surgery and the results depend on the etiology, intensity, site and time of treatment of facial palsy.

REFERENCES

Bleicher JN, Hamiel S, Gengler JS, Antimarino J. A Survey of Facial Paralysis: Etiology and Incidence. Ear Nose Throat J 1996;75:355-8.

Van Swearingen JM, Brach JS. The Facial Disability Index: Reliability and Validity of a Disability Assesment Instrument for Disorders of the Facial Neuromuscular System. Physical Therapy 1996;76:1288-300.

Brandel P, Saloretti-Schefer S, Bohmer A, Wichmann W, Fisch U: Correlation of MRI, Clinical and Electroneurographic Findings in Acute Facial Nerve Palsy. Am J Otol 1996;17:154-61.

House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial Nerve Grading System. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985;93:146-7.

Mountain RE, Murray JA, Quabba A, Maynard C. The Edinburgh Facial Palsy Clinic: A Review of Three Year's Activity. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1994;39:275-9.

Pulec JL. Iatrogenic Facial Palsy: The Cost. Ear Nose Throat J 1996;75:730-6.

Wormand PJ, Nilssen EL: Do the Complications of Mastoid Surgery differ from those of the Dissease? Clin Otolaryngol 1997;22:355-7.

De Bonfils-Dindart C, Darrouzet V, Mbarek C, Dumon T, Diab S, Bebear JP. Management of Post-traumatic Facial Paralysis. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 1995;16:171-7.

Hartley C, Mendelow AD. Post-traumatic Bilateral Facial Palsy. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:730-1.

Ross BG, Fradet G, Nedzelski JM. Development of a Sensitive Clinical Facial Grading System. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;114:380-6.

Engstrom M, Jonsson L, Grindlund M, Stalberg E. House-Brackmann and Yanagihara Grading Scores in Relation to Electroneurographic results in the Time Course of Bell's palsy. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1998;118:783-9.

Qiu WW, Yin SS, Stucker FJ, Aarstad RF, Nguyen HH. Time Course of Bell's Palsy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:967-72.

|

Pro Otology |

Journal Home Contents Preview Next |